The dominion area of the Etruscans in north Italy developed in two directions. The first towards the Alpine passages, that allowed the relations with central Europe; the second towards the Adriatic Sea, in particular the delta of the river Po. It was the traditional docking and exchange area of Mediterranean navigation routes, in particular of the Greek ones.

Spina was founded short before the end of VI century BC. Its favorable position- at that time situated at the confluence of river, sea and terrestrial routes (Reno, Po and the Adriatic Sea)- made it the perfect spot for the foundation of a port-emporium.

The relations with the Greek world and Attica lasted for a long time without perceiving the crisis that caught the Etruscan world at the beginning of the IV century, with the arrival of the Gallic tribes in the padana plain. The decline begun in the III century BC when a Gallic siege worsened the problems coming from the difficulty to open a way towards the sea. From that time, until the beginning of the I century bC, Spina survived as a small village.

Spina was then an emporium, the seat of a merchant community. The exchange of goods was primarily based on barter, in fact, it never coined its money. The excavations brought to light one single coin- a north Italian dramma, datable between the end of the III and beginning of the I century BC, coined by the Celts that occupied this territory.

Everything was bartered: figured Attic pottery, oil and wine, perfumes and ointments, marble from the isles, maybe even salted fish, honey, fabrics, exotic and luxury objects were exchanged with agricultural products, particularly wheat, from the fertile Po Valley. .

Many products sailed from Spina to Greece: salted pork and bovine meat, lumber, amber, Etruscan bronzes, leather, slaves, and maybe even fur and the famous Venetian horses.

The privileged relations between Athens and Spina seem to have developed in consequence to Athens’ need for raw materials, most of all grain. Regarding Spina, the most striking thing is the contrast between the wealth of imported materials used to equip tombs, and the poor aspect of the city. It’s obvious that it was profit, rather than the pleasantness of the landscape, that motivated the inhabitants to live in this city.

Even though mentioned in numerous Greek and Roman sources, the site itself was individuated only in 1922, when the drainage of Valle Trebba brought to light the first objects that could be attributed to the necropolis of the Etruscan city. The excavations unearthed 1213 tombs, which have to be added to the approximately 200 found between 1962 and 1965. In the ‘50s the drainage of Valle Pega, south of Valle Trebba, evidenced the presence of another sector of the necropolis, containing 2650 tombs.

The area of the town was discovered in the ‘60s during the drainage of the Valle of Mezzano.

The tomb equipments of V and IV century

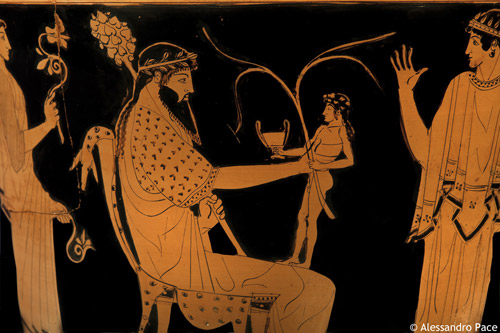

The most striking element of the fifth century tomb equipment is not so much the Attic black-figure pottery as the red-figured one which includes some of the best works realized in Athenian workshops in that time. The important vases of Spina dated between 480 and 400 BC are, according to Sir John Davidson Beazley, the most important collection of that time in the world.

The presence of Attica red-figured ceramics characterizes Spina tombs until the half of IV century BC, when it begins to diminish, until its complete disappearance. This phenomenon is related to a significant change in commercial flows –in fact Attica pottery is progressively being replaced by the one from Etruria. Vases painted in black, imported in grand quantity originated from Volterra, while those figured, less frequent, are produced in Volterra and Chiusi. These objects are usually smaller, more suitable for terrestrial transport across the Appenine passes. Around the middle of IV century the presence of Greek pottery decreases but simultaneously the number of locally manufactured materials increases. Particularly striking for its abundance and grand variety, is the northern-Adriatic pottery. These materials are to be added to the imports from Magna Graecia, particularly from Apulia, from where, since the end of V century, figured vases in small and large dimensions arrive at Spina, and probably also luxury items like jewellery, balsam containers, ointments and perfumes.

The phases of the discovery of Spina went together with the drainage of the lagoons surrounding Comacchio, now fertile lands where the intensive farming has almost completely erased the vestiges of the previous population. First to come to light was the necropolis of Valle Trebba (1922-1935), followed by the necropolis of Valle Pega (1954-1960), and finally the town (with the drainage of Valle Mezzano, 1960). The settlement rose on the right shore of Po, taking advantage of the irregular conformation of a hillock that we can imagine emerging from the lagoon, maybe surrounded by minor hillocks. Massive wooden pilings reinforced the perimeter, poles placed in the clay, foundation beams, sticks, canes, and barks drained and consolidated the ground where the houses rose, with walls consisting of a wooden framework and pressed clay. The house covering was just as light.

Canals and paths, some of which cobbled, intersected one another among these buildings, which probably during the advanced V sec. B.C. were reshaped according to a system which gave the city a regular orthogonal arrangement. The fragile and modest aspect of the buildings, torn down and raised over and over again because of frequent floods and fires, is the keynote of the city. Our knowledge of it is limited to its living quarters and some commercial areas, none of which expressed anything monumental. The same can be said for the necropolis that stretched on the sand dunes a few kilometers east of the town, which the branch of the Po River itself had formed.

In both rituals, cremation and inhumation, the dead were buried in pits, at times marked by an anepigraphic tombstone in marble or limestone (stones, small columns, more frequently river pebbles). Only the larger dimension of the pit and the number or valuable objects that accompanied the deceased on his journey to the Underworld, or adorned their clothes or body, marked the wealth that at other sites was declared with an external grandiloquent apparatus.

The richness of these tombs is therefore in their "equipment", where the overwhelming presence of painted Attic pottery from V and IV century BC come together with fused bronzes and laminates (candlesticks and vases of various shapes), balm containers in glass paste and alabaster gypsum, amber and jewelry, more modest but no less significant ceramics of the local manufactures as well as the household goods that came to Spina from other peninsular areas (Veneto, Sicily and Southern Italy, Etruria) and Greece (Corinth and Boeotia, for example).

The city, center of storage and sorting of goods, a short distance from the sea, on the river, was therefore a peculiar expression of the solid and far-sighted political and economic power established by the Etruscans in the eastern part of the Po Valley, its "Greekness” resided in a deep and widespread uptake of Attic culture. The short history of Spina is accomplished in less than three centuries; founded towards the end of the sixth century BC, and at the height of its economic development in the period between the second half of the fifth and the first quarter of the fourth century BC, declined in the third century BC, the last bastion, in northern Etruria, to fall under the pressure of the Gallic populations.

The National Archaeological Museum of Ferrara takes up these topics by presenting, in the rooms of the first floor, specimens of the materials of some of the most interesting tombs of the necropolis. They are displayed according to a chronological order, starting from the earliest period, and, in the correlation with their constitutive objects, express the change of habits through the filter of different social roles played by individuals in the community. Even more emblematic, as an index of their wealth and their acculturation, is the presence of those monumental vases, the result of the creativity of the most popular and active masters of the Keameikos quarter, whose epic and mythological depictions overshadow with their own celebratory language the political events and power of contemporary Athens.